Background

The Cold War emphasis on containment is often framed in terms of Truman’s foreign policy decisions: the Marshall Plan and Truman Doctrine in Europe, the Korean War in Asia. Yet containment took on a life of its own in the United States as many Americans grew more and more concerned about Communism on U.S. soil, and even more alarmingly, in government agencies. The rise of McCarthyism in the wake of this fear is well-known. Less discussed, perhaps, is the emergence of a Loyalty Program within the federal government.

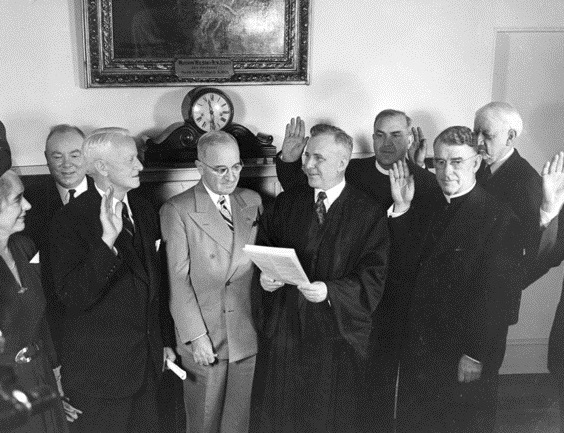

Truman’s Loyalty Program has its origins in World War II, particularly in the Hatch Act (1939), which forbade anyone who “advocated the overthrow of our constitutional form of government in the United States” to work in government agencies. After the war, tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union grew, as did suspicion of workers in every government department. Several advisors, including Attorney General Tom Clark, urged Truman to form a loyalty program to safeguard against communist infiltration in the government. Initially, Truman was reluctant to form such a program, fearing it could threaten civil liberties of government workers. However, several factors shaped his decision to institute such a policy. Fear of communism was growing rapidly at home, and in the 1946 midterm election, Republicans gained control of Congress for the first time since 1931. To examine the issue, in November 1946 Truman created the Temporary Commission on Employee Loyalty, which stated, “there are many conditions called to the Committee’s attention that cannot be remedied by mere changes in techniques… Adequate protective measures must be adopted to see that persons of questioned loyalty are not permitted to enter into the federal service.” In March 1947, Truman signed Executive Order 9835, “prescribing procedures for the administration of an employees loyalty program in the executive branch of the government.”

The Loyalty Program has been criticized as a weapon of hysteria attacking law-abiding citizens. The Attorney General’s office compiled lists of “subversive” organizations, and prior involvement in protests or labor strikes could be grounds for investigation. As the Cold War intensified, investigations grew more frequent and far-reaching. As noted in Civil Liberties and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman, edited by Richard S. Kirkendall, “During the loyalty-security program’s peak years from 1947 to 1956, over five million federal workers underwent screening, resulting in an estimated 2,700 dismissals and 12,000 resignations… the program exerted its chilling effect on a far larger number of employees than those who were dismissed” (70).

While Truman feared the Program could become a “witch hunt,” he defended it as necessary to preserve American security during a time of great tension. Many Americans agreed with him and applauded his stand against communism and subversion. The historical context of this event is important, for every investigation, every loyalty oath and every questionnaire took place under a backdrop of fear in an uncertain post-war world.

It is common today to look at events like McCarthyism, HUAC and the Loyalty Program as products of hysteria. Yet this hardly was the first time the federal government restricted civil liberties in the name of national security. In 1798, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts as concerns grew over a looming war with France. During both the Civil War and World War I, individuals suspected of disloyalty faced prison. The liberty vs. security debate is a continuity in American history, and even though we live in a post-Cold War world, some of these issues are still part of the discussion in an age of global terrorism. Truman’s Loyalty Program must be viewed and debated with this understanding, and the understanding that historical context drives presidential decision making.

Key Question

Do Cold War fears during the Truman Administration justify the institution of the government Employee Loyalty Program in a democratic society?

Materials

Documents to be examined:

- Report of the President’s Temporary Commission on Employee Loyalty, November 26, 1946

- Executive Order 9835, March 22, 1947

- David J. Sloane to Harry S. Truman, May 28, 1947

- Advertisement, “Leading Americans Warn of Dangers in Order 9835”

- Frank B. Steele to Harry S. Truman, with Attachment and Reply from Matthew J. Connelly, July 7, 1947

- J. Parnell Thomas to Harry S. Truman, September 29, 1948

- Albert B. Epstein to Harry S. Truman, with Attachment, March 31, 1948

- Walter White to Harry S. Truman, November 26, 1948

- Letter from Laurence Jaeger to President Truman, August 4, 1952

- Petition to Harry S. Truman and U.S. Congress