By John W. McDonald

Former editor of The Examiner

Independence Examiner Truman Centennial Edition May 1984

"It was on the farm that Harry got his common sense. He didn't get it in town."

Thus did Martha Truman describe the experience of her son who for 11 years operated the family farm at

Grandview, 20 miles southwest of Independence. She added that he would "plant the straightest row of corn in the whole country."

His proud mother put her finger on a trait that stood out in the public service career of Harry S. Truman - from his days as county judge to those of world leadership in the critical period following World War II. "Common sense" was a factor in the decisions he was called on to make.

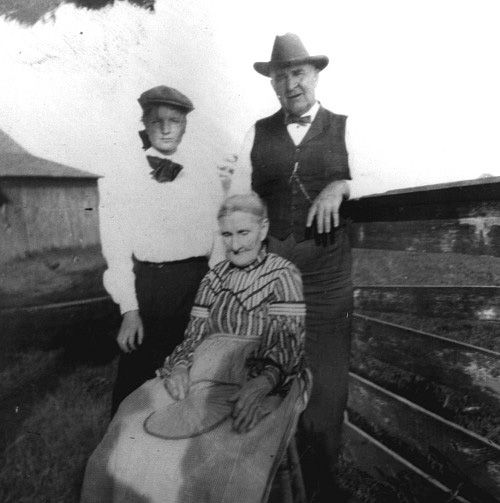

Mr. Truman left a Kansas City bank job and went to Grandview in the summer of 1906 when his father asked him to help manage the farm belonging to his widowed grandmother, Louisa Young. His parents had moved from Clinton, Mo., to the farm a year earlier to help Grandmother Young.

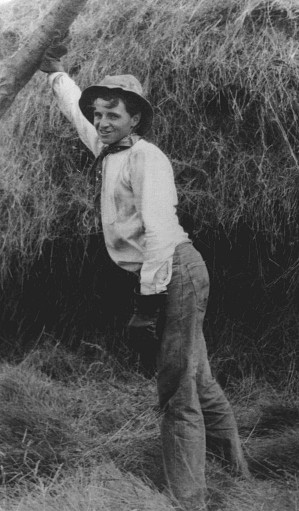

Mr. Truman was 22 then, and apparently had no regrets about leaving the city for the life of a farmer. He showed by his actions he was proud of the vocation; he considered tilling the land a completely honorable calling. Until his father, John Truman, died in 1914, Mr. Truman had his advice and assistance. But after that, he shouldered full responsibility for the farm operation until he left for war in 1917.

Mr. Truman's brother, Vivian, came back to the farm, too, but returned to a bank job the next year. After a brief return to the farm, he moved away in 1911 when he married. Uncle Harrison Young had left the farm for an easier life in the city.

When Grandmother Young died in 1909 at age 91, she willed the farm to Mr. Truman's mother and Uncle Harrison, cutting off other members of the family with $5 apiece.

They contested the will with legal action that was drawn out over several years. Finally Martha Truman settled with them out of court by assuming several mortgages for cash to pay them in exchange for quitclaims.

Mr. Truman approached his rural responsibilities with enthusiasm and intelligence and worked hard to improve the farm. The farm had been very fertile, but he increased its fertility by crop rotation, soil conservation and weed control. He instituted record keeping of actual costs per acre on crops, and he used labor-saving equipment instead of hiring more farmhands.

Later he recalled that he plowed, sowed, reaped, milked cows, fed hogs, doctored horses, baled hay and did everything there was to do on a 600-acre farm.

Mr. Truman's courtship of Bess Wallace started and flourished during his years on the farm. He made many weekend trips to Independence to see her and kept the mails hot with letters. These letters were released and published in a book entitled "Dear Bess," and edited by Robert Ferrell. The letters make no apologies for his occupation as a farmer.

He told Bess about the daily jobs that occupied his time. He found humor in farm life and spiced his letters with folksy passages, such as a prescription for dipping chickens given to him by his "Mama."

Mr. Truman also learned the physical hazards of farming. He suffered a broken leg while setting fence posts when a 400-pound calf bolted and ran into him. This meant several weeks of immobility, during which he was able to devote more time to writing to Bess.

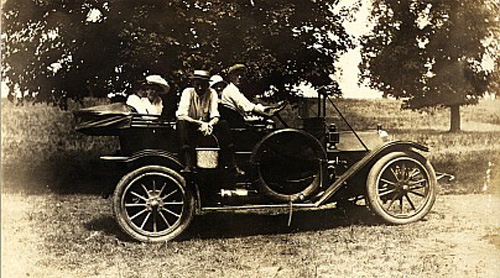

The trips made to Independence were time consuming and arduous. It was a 20-mile journey that he traveled either by train or streetcar. However, this problem was eased when he bought a used Stafford automobile. The car provided transportation on outings for Harry and Bess and their young friends.

Despite the hard, tiring work on the farm, Mr. Truman had too much energy to restrict himself to farming; his interests covered a wide range of activity.

Mr. Truman's horizons weren't at the edge of the farm. He managed to continue his reading, was involved in the National Guard and started going to night meetings of the 10th Ward Democratic Club in Kansas City headed by Mike Pendergast. He joined the Masonic Lodge at Belton and organized a new lodge at Grandview. There were good crop years and bad crop years, but profits from the farm never were excessive.

When Uncle Harrison died in 1915, he left his half interest on the Young farm as well as 300 adjoining acres that he owned to Martha Truman and her children - Harry, Vivian and Mary Jane.

World War I marked a turning point in Mr. Truman's career. After the armistice was signed, he returned briefly to the farm. He never again was directly involved in farming.

Instead of continuing as a dirt farmer, Mr. Truman eventually became president of the United States.