Harry Truman’s own modest background, reinforced by his appreciation for the shared sacrifices of ordinary fellow Americans during the Second World War, led him to endorse initiatives favoring the common man over business elites. The idea of “fairness” was a guiding principle for Truman. After the war, he sought to hold corporations accountable and address inequality. Yet Congress rejected his ambitious 21-point domestic agenda. In 1948, his growing awareness of racial violence led him to desegregate the military and civilian Federal government workforce by executive order. This marked a historic turn in the Democratic party toward support for civil rights.

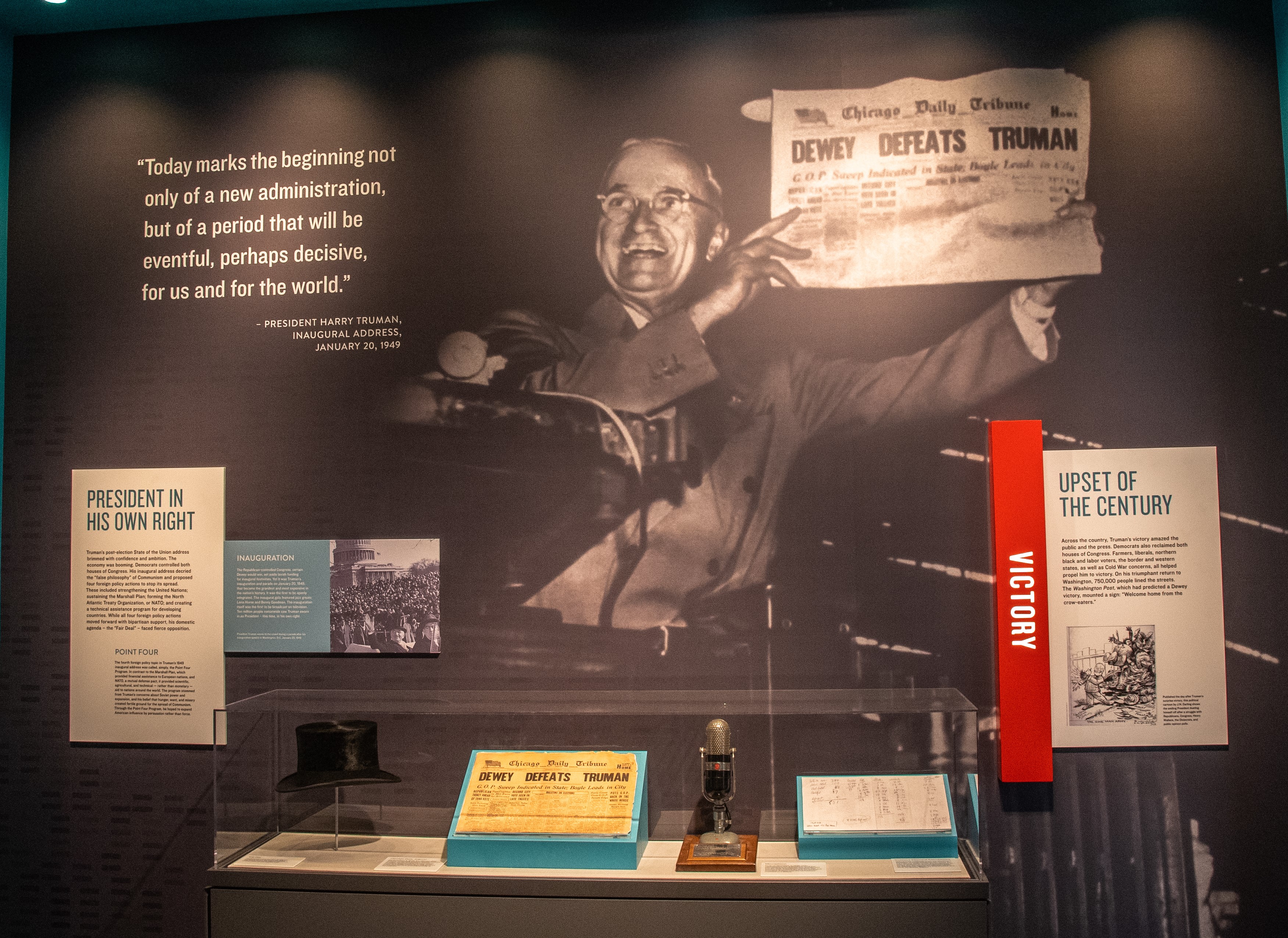

The nation was stunned when the underdog Truman won his 1948 election campaign. As president in his own right, he rebranded his agenda the “Fair Deal.”

Harry Truman’s background did not suggest he could become a champion of civil rights. Growing up in a segregated environment, he did not believe in social equality between races. His early letters included racial slurs. He even met with the Ku Klux Klan during his first run for political office. As a senator, he promoted segregated public housing. Yet he also spoke of “brotherhood of all men before the law.” As a veteran himself, President Truman was infuriated by brutal lynchings and abuse of veterans of color. He authorized a civil rights committee and called for anti-lynch laws and an end to poll taxes. In a groundbreaking set of executive orders he also desegregated the military and the civilian government workforce.

Key document:

To Secure these Rights: The President's Commission on Civil Rights

Key artifact: