This lesson can be integrated into classroom activities by individual students, cross curricular with Language Arts and/or as a cooperative learning endeavor. Students will analyze Internet websites and access links to a variety of primary and secondary documents.

- To assist students in developing analytical skills that will enable them to evaluate primary sources and images such as documents, photographs, political cartoons and posters related to the Japanese Internment Camps during World War II

- To introduce students to the Stanford History Educational Group’s Reading Like A Historian teaching strategies to help them investigate historical questions by employing the following reading strategies: Sourcing, Contextualizing, corroborating and close reading

- Analyze historical data through the use of primary source documents, posters, photographs and political cartoons

- Develop a sense of historical understanding of the internees' experiences during and after the Internment.

- Evaluate the themes of tolerance and prejudice towards the Japanese during World War II

- Scrutinize the implementation of Executive Order 9066

Omaha, NE Public Schools 9th Grade U.S. History Standards

01: Examine and analyze conflict and resolution both domestically and internationally in the 20th and 21st centuries 03: Interpret (writing, discussion and debate) primary and secondary sources

11th Grade. Modern History

04: Explain how certain cultural characteristics such as language, ethnic heritage, religion, political philosophies, shared history and social and economic system can link or divide regions and cause global conflicts in the 20th Century such as World War II and the Cold War

National United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources:

Standard 3: The causes and course of World War II, the character of the war at home and

abroad, and its reshaping of the U.S. role in world affairs

Thinking Standard 3: The student engages in historical analysis and interpretation:

Thinking Standard 4: The student conducts historical research:

Thinking Standard 5: The student engages in historical issues-analysis and decision-making

State: Nebraska

NE Dept. of Edu. http://www.education.ne.gov/ss/Documents/2012December7VerticalNE_SocialStudiesStandardsApproved.pdf

SS 12.4.2 (US) Students will analyze and evaluate the impact of people, events, ideas, and symbols upon

US history using multiple types of sources.

SS 12.4.2.c (US) Analyze and evaluate the appropriate uses of primary and secondary sources

SS 12.4.3 (US) Students will analyze and evaluate historical and current events from multiple perspectives

SS 12.4.4.a (US) Compare and evaluate contradictory historical narratives of Twentieth-Century U.S. History

through determination of credibility, contextualization, and corroboration

SS 12.4.5.b (US) Obtain, analyze, evaluate, and cite appropriate sources for research about Twentieth-Century

U.S. History, incorporating primary and secondary sources (e.g., Cite sources using a prescribed format)

SS 12.4.5.c (US) Gather historical information about the United States (e.g., document archives, artifacts,

newspapers, interviews)

SS 12.4.5.d (US) Present an evaluation of historical information about the United States (e.g., pictures, posters,

oral/written narratives and electronic presentations)

Common Core

http://www.corestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/ELA_Standards.pdf

Key Ideas and Details

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.3 Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

Craft and Structure

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.5 Analyze in detail how a complex primary source is structured, including how key sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text contribute to the whole.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.6 Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.7 Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.8 Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.9 Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

Smithsonian in Your Classroom. “”Letters from A Japanese American Internment Camp.” Pp. 42-60. Fall, 2002

Special Section: Fifty Years of United States-Japanese Foreign Relations. Social /Education. Pp. 433-458. November/December 1991.

The Home Front. World War II. Japanese American.” American History Illustrated. Pp. 31-34. July, 1979.

Ansel Adams’s Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/manz/

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/manz/background.html

Densho

Dorothea Lange. Omen Come to the Front. Japanese Americans

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/wcf/wcf0013.html

Internment Camps in America

http://www.teacheroz.com/Japanese_Internment.htm

Japanese Internment. Political Cartoons

https://www.thinglink.com/scene/637121647710568450

Korematsu v. United States. December 18,1944. http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0323_0214_ZO.html

Library of Congress. Japanese American Internment

http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/internment/

http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/internment/

National Archives. Teaching With Documents and Photographs Related to Japanese Relocation During World War II

http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation/

Smithsonian. Japanese American Internment

http://amhistory.si.edu/perfectunion/resources/touring.html#SECTION1

Stanford History Education Group. U.S. History Lessons. New Deal and World War II. “Japanese Internment.”

https://sheg.stanford.edu/new-deal-wwii

Sanford History Education Group. Japanese Internment lesson. Government newsreel: http://www.archive.org/details/Japanese1943

Teachinghistory.org Civil Rights and Incarceration.

http://teachinghistory.org/teaching-materials/lesson-plan-reviews/20013

The Munson Report, delivered to President Roosevelt November 7, 1941. http://home.comcast.net/~chtongyu/internment/generations.html

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: The Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians,” February 24, 1983. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/personal_justice_denied/index.htm

The Virtual Museum of the City San Francisco

http://www.sfmuseum.org/war/evactxt.html

Truman Library. Education Resources. Japanese Internment

UCLA. Institute on Primary Resources. Lesson plan Japanese American Internment.”

http://ipr.ues.gseis.ucla.edu/classroom/lessons.html

War Relocation Camps in Arizona

http://parentseyes.arizona.edu/wracamps/

Internet

Direct students to read about the internment of Japanese American in their textbook during World War II and provide students with a copy of the following background information.

For nearly a decade prior to the outbreak of war, various federal agencies had been conducting surveillance in Japanese American communities in anticipation of a possible war with Japan. The general consensus of those agencies was that the Japanese American community as a whole posed little threat to the U.S. should war with Japan take place. They also put together custodial detention lists of those who would be arrested should war come. These lists allowed the government to begin rounding up what were now “enemy aliens” within hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. For the most part, those apprehended were male immigrant community leaders who were suspect for the positions they held—heads of a Japanese Association branch or priests at Buddhist temples, for instance—rather than for anything they had specifically done. Initially held in local facilities—along with some prisoners of German and Italian descent—they were moved to internment camps run by the army or Immigration and Naturalization Service, with most spending the duration of the war there, sometimes alongside Japanese Latin Americans who had been evicted from their homes and brought to the U.S for internment.

Despite the swift arrest and detention of all whom prewar surveillance had identified as suspect, calls for stronger measures soon came from West Coast political leaders, who drew upon five decades of anti-Japanese sentiment. Such sentiment dovetailed with views held by General John L. DeWitt, the head of the army’s Western Defense Command, which was charged with the defense of the Western U.S. They influenced key figures in the War Department to advocate for removing all Japanese Americans from West Coast states. Though the Justice Department, led by Attorney General Francis Biddle, opposed such measures, the proponents of mass removal won out, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066—which gave the army power to exclude whomever it saw fit under the guise of “military necessity”—on February 19, 1942.

Armed with EO 9066, General DeWitt wasted no time in ordering the West Coast be cleared of Japanese Americans. At first, Japanese Americans were encouraged to move inland on their own, what the government called “voluntary evacuation.” Not surprisingly, leaders of other Western states objected, and this plan was called off after a mere 5,000 out of 110,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast had moved. Instead, the army’s Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) quickly created fifteen “assembly centers” and two “reception centers” to house the Japanese Americans. The “assembly centers” utilized existing facilities such as fairgrounds and horse racing tracks located near the areas where Japanese Americans were being removed. The WCCA efficiently removed Japanese Americans neighborhood-by-neighborhood over the spring and summer of 1942 in a series of 108 exclusion orders. Residents of the area defined by each order were given a week to tie up their affairs and report for their own exile. Stories abound of profiteers offering distressed Nikkei pennies on the dollar for their possessions or taking over farms filled with ready-to-harvest produce. As Japanese Americans got on the trains and buses, they wondered what the future held for them. http://www.densho.org/looking-like-the-enemy/

March 18, 1942: President Franklin D. Roosevelt issues Executive Order 9102, which establishes the War Relocation Authority (WRA) within the Department for Emergency Management. The WRA is empowered “to provide for the removal from designated areas of persons whose removal is necessary in the interests of national security….” The WRA is further empowered to provide for evacuees’ relocation and their needs, to supervise their activities, and to provide for their useful employment. Milton S. Eisenhower is named director of the WRA.

March 21, 1942:President Roosevelt signs Public Law 77-503, which makes it a federal crime for a person ordered to leave a military area to refuse to do so.

March 22, 1942:The first removal of people of Japanese descent from the designated Pacific Coast area occurs. The people are from the Los Angeles area; they are sent to the Manzanar relocation center in northeastern California. The center comprises a 6000-acre site, enclosed by barbed wire fencing, and within that site a 560-acre residential site with guard towers, searchlights, and machine gun installations. During the next eighteen months, about 120,000 people of Japanese descent are removed from the Pacific Coast area to ten relocation centers in California, Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.

March 27 to 30, 1942: The Western Defense Command issues proclamations which severely restrict the movements of persons of Japanese descent in the Pacific Coast military area, and which prohibit them from leaving the military area. The Western Defense Command had decided that allowing people of Japanese descent to leave the military area and go wherever they chose was creating too much disturbance and opposition among local people.

April 7, 1942: A meeting of WRA officials with representatives of eleven western states convenes in Salt Lake City, Utah. The representatives for the most part express distrust of and dislike for the people of Japanese descent who were being evacuated to their states. The WRA concludes that, because of this hostile local opinion, the evacuees from the Pacific Coast must be housed in evacuation camps guarded by the Army. During the meeting, the governor of Wyoming told the director of the WRA, “If you bring Japanese into my state, I promise you they will be hanging from every tree.”

Spring 1942: WRA administrators divide the people of Japanese descent in the Pacific Coast military zone into three categories: (1) Issei, immigrant Japanese born in Japan (about 40,000 in the military zone); (2) Nisei, American born and educated children of Issei parents (about 63,000 in the military zone); and (3) Kibei, American born but educated wholly or partly in Japan (about 9,000 in the military zone). A fourth category was Sansei, second generation American born, the children of the Nisei (about 4,500

April 24, 1946:The Truman administration sends to Congress proposed legislation which would establish an Evacuation Claims Commission to adjudicate claims against the United States for losses suffered by evacuees as a result of their removal from their homes and detention in relocation centers.

June

June 26, 1946: President Harry S. Truman signs Executive Order 9742, which terminates the WRA effective June 30, 1946.

February 2, 1948: President Truman sends to Congress a special message on civil rights in which he requests legislation to settle claims against the government by the 110,000 people of Japanese descent who were evacuated from their homes during World War II.

July

July 2, 1948: President Truman signs the Japanese-American Claims Act, which authorizes the settlement of property loss claims by people of Japanese descent who were removed from the Pacific Coast area during World War II. According to a Senate Report about the act, “The question of whether the evacuation of the Japanese people from the West Coast was justified is now moot. The government did move these people, bodily, the resulting loss was great, and the principles of justice and responsible government require that there should be compensation for such losses.” The Congress over time appropriated $38 million to settle 23,000 claims for damages totaling $131 million. The final claim was adjudicated in 1965.

Japanese Internment Timeline

http://sheg.stanford.edu/japanese-internment

1891

- Japanese immigrants arrived in the U.S. mainland for work primarily as

agricultural laborers.

1906

- The San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution to segregate

white children from children of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean ancestry

in schools.

1913

- California passed the Alien Land Law, forbidding "all aliens ineligible for

citizenship" from owning land.

1924

- Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, effectively ending all

Japanese immigration to the U.S.

November 1941

Munson Report released

December 7, 1941

- Japan bombed U.S. ships and planes at the Pearl Harbor

military base in Hawaii.

February 19, 1942

- President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066,

authorizing military authorities to exclude civilians from any area without

trial or hearing.

January 1943

- The War Department announced the formation of a segregated

unit of Japanese American soldiers.

January 1944

- The War Department imposed the draft on Japanese American

men, including those incarcerated in the camps.

December 1944

- The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Executive

Order 9066

March 20, 1946

Korematsu v. United States

.

–The last War Relocation Authority facility, the Tule Lake

“Segregation Center,” closed.

1980

- The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was

established

.

1983

- The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians

issued its report,

Personal Justice Denied

(Document E).

August 10, 1988

- President Ronald Reagan signed HR 442 into law. It

acknowledged that the incarceration of more than 110,000 individuals of

Japanese descent was unjust, and offered an apology and reparation

payments of $20,000 to each person incarcerated.

Provide students with a copy of the Stanford “Historical Thinking Chart.” Discuss with students how they can investigate historical questions by employing the following reading strategies: sourcing, contextualizing, close reading and corroborating.

.

http://sheg.stanford.edu/upload/V3LessonPlans/Historical%20Thinking%20Chart.pdf

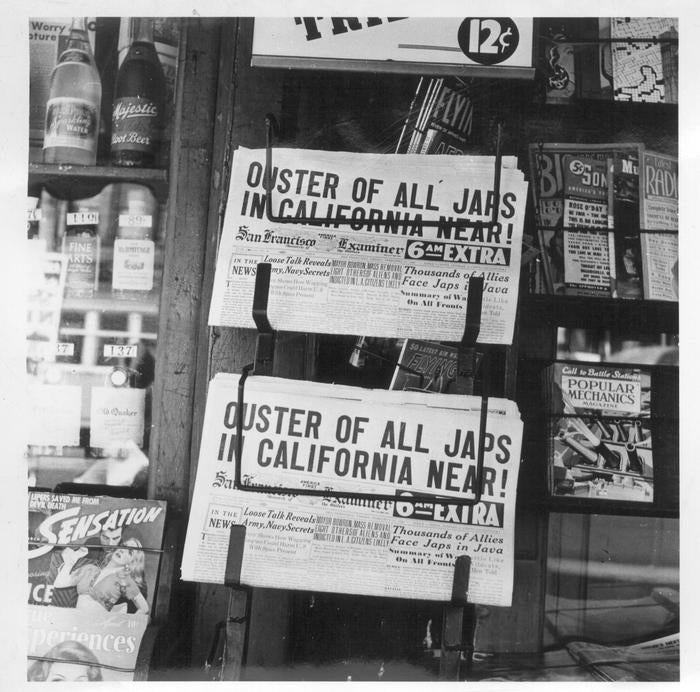

Provide students with a copy of the document titled “Ouster of all Japs in California Near.”

Library of Congress

http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a24566/

- Engage students in an evaluation of the preceding document using the following “Primary Source Analysis Worksheet”.

Primary Source Analysis Worksheet. Note: Similar form located at the National Archives http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/worksheets/written_document_analysis_worksheet.pdf

I. Type of Source (check one of the following)

A. Document

___ Newspaper ___ Telegram ___ Diary

___ Autobiography ___ Report ___ Oral History

___ Letter ___ Map ___ Advertisement

___ Gov. Document ___ Book ___ Other?______

B. Graphic

___ Photograph ___ Broadside ___ Artistic Presentation

___ Cartoon ___ Poster ___ Sheet Music

___ Painting ___ Print ___ Other?________

II. When was this source created? __________________________________

How do you know? ______________________________________________

III. Who wrote/created this source? _________________________________

How do you know? ______________________________________________

Did the creator of this source have first-hand knowledge of the events?

_____________________________________________________________

IV. In the space below, write a 2-3-sentence description of the source. Here are

some questions to help you.

Document: Is it printed, typed or handwritten?

If handwritten, can you read it?

Are there any notations in the margins?

Any special marks or seals?

Any other interesting characteristics?

Graphics: What people/objects/activities appear in the graphic?

What symbols/words/phrases appear in the graphic?

How are all of the above arranged in the graphic?

V. Who (do you think) is the audience for this source? _________________

Why do you think that? _____________________________________

VI. Do you think the purpose of this source was to inform? To persuade? To

entertain? A combination of these? ____________________________

Why do you think that? ______________________________________

VII. What additional questions do you have about this source? How could you find

the answers to these questions?

- Assign students to review the film created by the U.S. Office of War Information to explain the movement of Japanese Americans in the U.S. during World War II located at https://archive.org/details/Japanese1943

Instruct students to consider the following questions as they film :

a. Who is narrating the film?

b. How does the narrator justify the removal of the Japanese Americans from their homes and businesses?

c. How did the U.S. Government help the Japanese Americans relocate?

d. What word did the narrator use to describe the move of the Japanese Americans by the U.S. Government?

e. To what locations were the Japanese Americans moved and why those locations?

- What employment opportunities were made available for the Japanese Americans?

g. What conclusions did you make about the purpose of the film and was the U.S. Government successful

Option 1: Instruct students to select one of the following political cartoons and use the “Reading an Editorial Cartoon” listed below to analyze the cartoon.

Reading an Editorial Cartoon

1. What is the cartoon’s title or caption?

2. Who drew the cartoon?

3. When and where was it published?

4. What is familiar to you in this cartoon?

5. What questions do you have about this cartoon?

6. Editorial cartoonists combine pictures and words to communicate their opinions. What tools does the cartoonist use to make his or her point?

Humor Labels

Caricature _ Analogy to another historical or

_ Symbols current event

_ Stereotypes _ References to popular culture, art,

_ Speech balloons literature, etc.

7. List the important people and objects shown in the cartoon:

8. Are symbols used? If so, what are they and what do they mean?

9. Are stereotypes used? If so, what group is represented?

10. Is anyone caricatured in the cartoon? If so, who?

11, Briefly explain the message of the cartoon:

12. What groups would agree /disagree with the cartoon’s message? Why?

13. Do you think this cartoon is effective in its message?

Source: The Opper Project. Reading an Editorial Cartoon

http://hti.osu.edu/opper/downloads/Editorial%20Cartoon%20Analysis%20Worksheet.pdf

Links to cartoons to use

Think Link

https://www.thinglink.com/scene/637121647710568450

Photobucket

http://s717.photobucket.com/user/journeymandkos/media/MentalInsecticide.jpg.html

Option 2

Instruct students to create a political cartoon related to the internment of Japanese Americans during World /War II. Provide students with a copy of the Rubric for evaluating political Cartoons and inform them it will be used to evaluate their political cartoon.

RUBRIC FOR EVALUATING POLITICAL CARTOONS

|

CATEGORY |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Poster Details |

The name, source and Web address of the poster are credible and cited correctly. |

The name, source and Web address of the poster are credible and most of the information is recorded correctly. |

The name, source and Web address of the poster are included but the citations are incorrect. |

The name, source or Web address of the poster are missing. |

|

Focus on Analysis |

There is one clear, well-focused topic. Main idea stands out and is supported by detailed information. |

Main idea is clear but the supporting information is general. |

Main idea is somewhat clear but there is a need for more supporting information. |

The main idea is not clear. There is a seemingly random collection of information. |

|

Support for Topic |

Relevant, telling, quality details give the reader important information that goes beyond the obvious or predictable analysis. |

Supporting details and information are relevant, but one key issue or portion of the analysis is unsupported. |

Supporting details and information are relevant, but several key issues or portions of the analysis are unsupported. |

Supporting details and information are typically unclear or not related to the analysis. |

|

Grammar & Spelling |

Writer makes no errors in grammar or spelling that distract the reader from the content. |

Writer makes 1-2 errors in grammar or spelling that distract the reader from the content. |

Writer makes 3-4 errors in grammar or spelling that distract the reader from the content. |

Writer makes more than 4 errors in grammar or spelling that distract the reader from the content. |